I once saw an advertisement for Humble Oil – now Exxon – in LIFE magazine (published 2nd February 1962) that proudly proclaimed ‘Each day Humble supplies enough energy to melt 7 million tons of glacier!’ The grim tragedy today of course, is the accelerated energy consumption, production of waste and overrun of nature that continues at an even faster pace than in 1962.

Glaciers and their disappearances make significant appearances in artists’ concerns throughout this exhibition – the retreat of these majestic forms of ancient frozen water heralds huge uncertainties that scientists struggle to come to terms with. This Viewing Room, Retreat, features artists whose various approaches to the phenomena of the unknowable territory that the melting north and south will bring us, asks us to contemplate what we do know about the accumulative effects of our consumption habits.

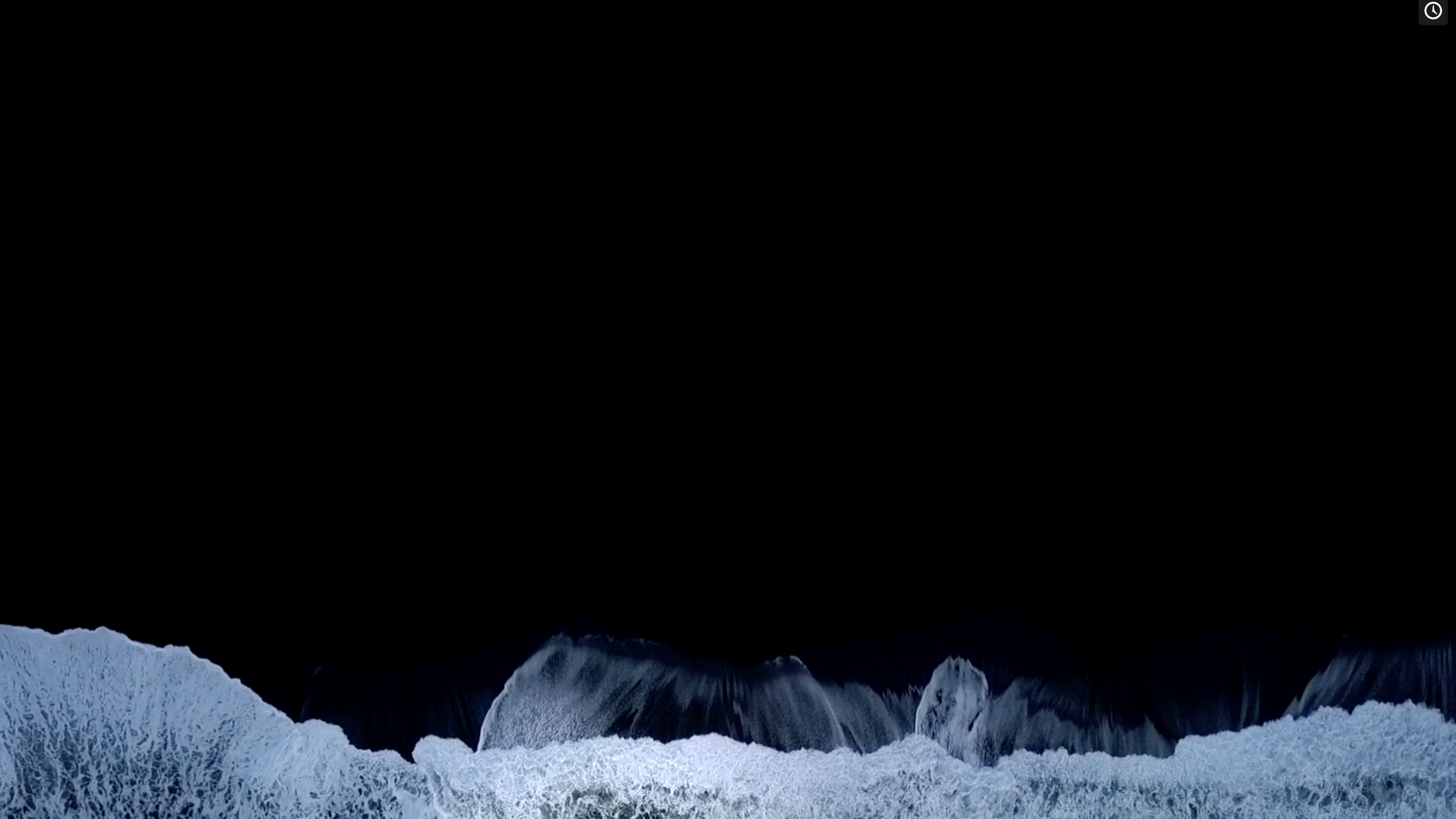

Angela Gilmour’s photopolymer etchings have a ghostly quality that recalls early 19th century sublime photography but to the contemporary eye, serves to remind us how much our perceptions and values of land and notions of wilderness have shifted irrevocably.

That we need to take better care of nature is evident in all the artists’ projects presented – we are nature after all, we share the same carbon that forms all organic forms on planet earth.

Anna Macleod, February 2022